The most common cattail (Typha latifolia) that we all recognise is a tall plant often found growing in dense stands in wetland areas, such as marshes and bogs. Various other species of cattail are found worldwide.

General Characteristics:

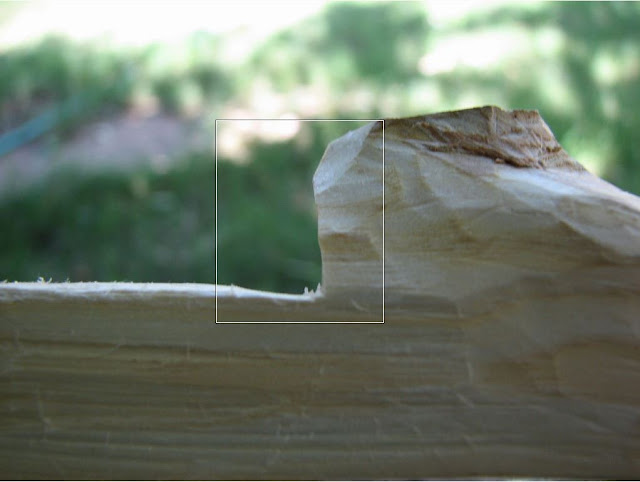

The very recognisable and familiar cattail flowers begin as green spikes (female parts) with loose, dangling hairs containing pollen (male parts) above that. Once fertilised, the female parts turn dark brown and the male parts fall away, leaving a stiff, pointed spike. The leaves are very tall and narrow (grass-like). A tall marsh plant, that grows in dense groups. Early in the year, the top of the head has a slender tail of lighter coloured staminate flowers, the lower dark brown area being tightly packed pistillate flowers. In fact, the flowers are very prolific, one stalk will produce an estimated 220,000 seeds. Even with this number of seeds, cattails colonise by sending up clones from the creeping rhizomes. It has been recorded that a cattail marsh can travel up to 17 feet in a year with prime conditions through the cloning process. Colonisation can happen quickly, as one new seed produces a plant, that new shoot in its first year will send out rhizomes for ten feet in all directions and can produce 100 clones in that first growing season. Cattails can reach heights 3-9 feet.

There are some poisonous look-alikes that may be mistaken for cattail, but none of these look-alikes possesses the brown seed head.

Blue Flag (Iris versicolor) and Yellow Flag (Iris pseudoacorus) and other members of the iris family all possess the cattail-like leaves, but none possesses the brown seed head. All members of the Iris family are poisonous. Another look-alike which is not poisonous, but whose leaves look more like cattail than iris is the Sweet Flag (Acorus calumus). Sweet Flag has a very pleasant spicy, sweet aroma when the leaves are bruised. It also does not possess the brown seed head. Neither the irises nor cattail has the sweet, spicy aroma. I have seen large stands of cattails and sweet flag growing side by side. As with all wild edibles, positive identification is essential. If you are not sure, do not eat it.

The list of uses for this plant is quite extensive and it has been said that if a lost person has found cattails, they have four of the five things they need to survive: Water, food, shelter and a source of fuel for heat—the dry old stalks. The one item missing is companionship. Some of the plant's major uses are:

Food source

The stems a few inches above the soil line in early summer are young and tender and can be peeled and eaten raw or boiled. The roots are great as well, simply pull the lower stalks until the roots break free, peel and eat raw or boil. The cattail will also develop flower heads that can be eaten by roasting as if you would an ear of corn. By mid to late summer, pollen will collect on the heads and it is easily shaken loose into any container to be used like flour to make bread, pancakes and can be used for thickeners in gravies and sauces. The roots in late fall and early winter can be mashed and soaked in water to release the starch. The starch will settle on the bottom and will resemble wet flour. Drain the water off and make bread, by adding a little pollen or add to clean water to make soup. Cattails are an ideal survival food because they are easily recognisable and grow practically anywhere there is water.

Shelter Material

The green leaves can be cut and woven together into shingle like squares for covering a shelter roof. The material will provide protection from the rain, snow and the wind even after it has dried. Weave a sleeping mat by making two long mats. Connect the mats on one side so it can be folded like a sleeping bag. Before folding over fill one side with pine boughs or other material suitable for sleeping on and then fold the empty half over and tie off so the “stuffing” is secured inside. You can fold the mat up and carry it with you if you have to break camp for another location.

Medicinal Uses

Cattails are truly a survival plant in the truest sense of the word. They not only provide, food, material for shelters and cordage cattails have medicinal uses as well. To treat burns, scrapes, insect bites and bruises split open a cattail root and “bruise” the exposed portion so it can be used as a poultice that can be secured over the injured area.

The ash of burnt cattails is said to have antiseptic properties and many people have used the ashes to treat wounds and abrasions. If you look closely at the lower stems you will notice an amber or honey like substance that seeps from the stem, use this secretion to treat small wounds and even toothaches, because it also has antiseptic properties.

Baskets or Packs

You can get creative and weave baskets or small packs for carrying food or other items. Cross a number of leaves together and once you have the base the size you want you would fold the pieces up and then weave around the sides to secure the shape. You can easily weave handles or straps into the basket/pack. The basket will become stronger as the cattail leaves dry and harden.

Cordage

Peel strips from the leaves and allow them to dry somewhat. Once dried braid at least three strips together to create a line for fishing or use in shelter building.

As you can see there are many edible and useful parts of the cattail, but now we are going to take a look at the uses for the fluff from the seed head:

Tinder

Once shredded from the seed head, the cattail fluff expands into a soft, string-like material – perfect for trapping sparks to create a campfire. Ensure you mix some other material with it as well. However, cattail fluff can burn very quickly, sometimes too quickly!

Charcloth

For starting a fire with old-fashioned flint and steel sets, or when using a magnifying glass to intensify the sun’s rays to start a fire, Charcloth is an ideal product to use.

The steps to create this handy material are quite simple; just pack a metal box with cattail fluff, pierce the box with a nail to make a small hole, then place the box into a campfire for 5 minutes. Use a stick or rod to remove the box from the campfire after some time, then let it cool. Now you have a premium Charcloth!

Lamp wicks

The first people to roam America were the Paleoindians, and they had many resourceful ways to survive in the harshest conditions of the New World.

A simple oil lamp was one way that they lit their caves and rock shelters. A pinch of cattail fluff rising up out of oil made for a fine wick. Try it yourself! If for any reason you don’t have any ‘mammoth’ fat, try a block of lard with a cattail wick.

Insulation

You can use cattail fluff inside any item for warmth, such as your hat, some of your clothes, or your footwear. It’s like a plant-based variety of insulation.

Insect Repellent

In certain situations, the smoke from the seed head of a smouldering cattail can be a substitute for insect repellent. On a fire safe surface, put the smoking cattail head upwind from your location and the bug repelling smoke will waft over you for 20-30 minutes. You can even leave the seed head attached to the stalk and stick it in the ground as a stand.

Have you tried using cattail for any projects? If so, please tell me what you did by leaving a comment